E-mail, mail list servers, and discussion boards are

messaging systems, where notes are mailed from one person to the others or are

posted on an electronic bulletin board for others to see. Such communication supports

collaboration and community building only in a limited way.

Currently, the discussion board is the de facto standard tool in distance education. Typically, an instructor posts a

provocative topic and asks the students to post opinions on the topic. All postings are e-mail messages,

differing from regular e-mail in that this is a community mailbox, not readily

accessible by unauthorized users such as spammers.

Most of this chapter will be

devoted to discussion boards and shared-document computer conferencing (SDCC)

systems, because these have the most usefulness for education.

What's Wrong With Discussion Boards

Limited Word Processing

These systems do not typically use a full-featured

word processor and in many cases are limited to typing text messages into form

fields. As a consequence, students

may not be able to create hyperlink interfaces with the Web, insert

graphics/sound clips/video clips, run spreadsheets, or perform other

educationally valuable activities in the electronic environment.

Awkward Environment for Responding and Dialog

Discussion boards afford only a clumsy way for

students to respond to each otherís postings. Students cannot directly edit each otherís messages. There is no way to annotate any given

note in context; one must create a new note and place it in the appropriate

place in the topic outline. Students

cannot even refer to each otherís content without cutting and pasting text from

the e-mail being referenced.

Discussion boards organize information only by some

arbitrary scheme, such as a topic outline. Specific places in the outline serve as fixed pigeonholes

for each message. There is no way

to create links outside of the hierarchical outline. Messages attach as notes associated with other notes, rather

than as Web-like links to notes associated with specific character strings

within a given document. There may

also be severe constraints on the use of graphics and multi-media

materials. The typical software

collects and files messages but does not mediate the group construction of an

academic deliverable, such as a group plan, project, report, or case study.

Each discussion board message has to be opened and

then closed separately. With many

systems, you cannot see what it is in one note while simultaneously viewing the

note to which it refers.

Poor Pedagogical Support

These limitations underlie a more serious deficiency

in the way discussion boards are used for teaching. As typically used, the bulletin board environment encourages

students to express mere opinions.

This trivializes learning.

Opinions do not promote critical or creative thinking unless they are

accompanied by data, and rigorous intellectual analysis.

Commonly, the purpose of on-line discussions is

unclear and the expectations are vague.

A few students can dominate the discussion. Comments are often weak, irrelevant or off task. No compelling need motivates students

to read all the postings and therefore much of the discussion is wasted for

many students. I remember an

Educational Technology conference presentation where the speaker showed the

Contents page of his discussion board, boasting about all the student postings

in his course. He failed to point out all the little yellow "new" tags, which indicated that he had not read the contents of those messages. The

problems of engaging students in on-line discussion prompted me to specify

devices that teachers can use to get students more involved in on-line

discussion (Klemm, 1998a).

A major reason for the trivial use of discussion

boards is that it is difficult for a group to DO anything on bulletin

boards. Teachers find it difficult

to use bulletin boards to help student learning teams make a decision, develop

a plan, conduct a project, write a report, conduct a case study, construct a

portfolio, or most of the other kinds of constructivist activities that rigorous

student-student interaction can enable.

Discussion boards do not facilitate the two key

pedagogical elements of building learning communities: collaborative learning

activities, and performing a constructivist task that creates an educational

deliverables. We teachers like to

say that we want our students to be creative and critical thinkers, but we opt

out when given the opportunity to teach those skills. I have seen numerous discussion boards where the teacher

does not structure conversation that requires back-and-forth dialogue among

students. Feedback from the

teacher is often lacking. In many classes, most students do not even participate, acting as "lurkers" who may or may not even be reading the postings.

A common teacher response to lurking is to require a specified number of

postings, which of course can easily degenerate into a game where students just

go through the motions of conversing.

E-mail and threaded-topic message boards fail to

compensate for the lack of personal interactions that typically occurs in a

traditional classroom and campus setting.

In general, Internet courses still emphasize a "delivery" mode of teaching (instructivism reigns supreme), as opposed to a "participatory" mode (Klemm, 1998b). In a participatory

mode, students interact with each other to develop understanding and construct

a communal base of information and understanding. Usually, this means that there must be a tangible result, a

deliverable of some sort that the learning teams produce. In short, such learning is

constructivist and collaborative.

Nothing fundamental is likely to change if a traditional,

teacher-centered teacher moves a course to the Internet. Indeed, the inadequacies of teacher

centeredness are magnified in an on-line environment.

What Is Right About Shared-Document

Conferencing

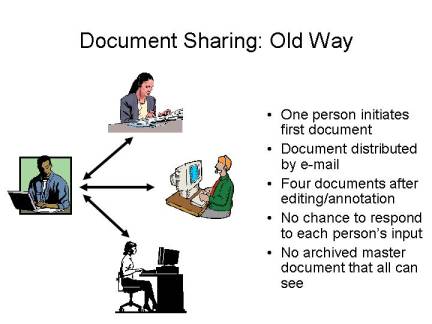

We are not talking here about e-mailing documents

around to each member of a learning group for their input. As shown in Fig. 1, this is hardly

convenient.

If multiple versions of the document have to be

created, then the disadvantages are compounded. Moreover, this crude approach does not provide an

environment for creating or re-structuring student groups, or for hyperlinking

sets of shared documents.

Figure 1.

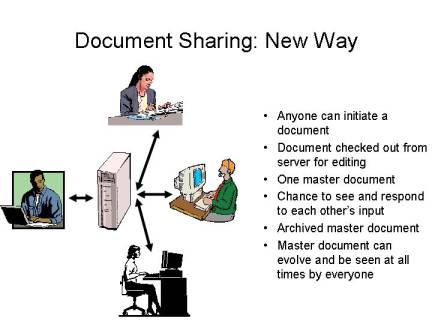

The modern solution is to have documents on a file server that can be "checked out" to be worked on asynchronously by group members. This model is shown in

Fig. 2.

Shared-document computer conferencing (SDCC)

overcomes the limitations of bulletin boards. The basic advantage arises from allowing students to share

documents completely; that is, they can not only read each otherís documents,

but they can also edit each otherís documents. The documents can become community documents. Yet, by adjusting permission settings, some documents may be "read only."

All editing is done with the same software editor in which the document

was created and can include making deletions, additions, and in-context

comments.

Figure 2

A key feature is the existence of a full-featured

word processor that supports multiple fonts, type sizes, tables, and

graphics. Students can insert

text, data tables, graphics, and sound or video clips into appropriate places

in the shared documents. They can

make links to Web pages and perhaps to other documents in the system.

SDCC systems move students away from the limited

discourse available with bulletin board notes. Maintaining a working memory of the intellectual content is

facilitated, because everything can be seen in one self-contained

document. At worst, one only has to

scroll up and down to see the various facts and ideas contained therein, which

is far more convenient that having the same content put in separate e-mail

messages that have to be opened and closed one at a time, obliging the reader

to remember what information is in each posting.

Most importantly, responses to points made by others

in the group can be done in context, in the form of pop-up notes for example

that still let you see the original text of what is being responded to and the

context in which that is embedded.

Such software provides shared workspaces for the

insertion and iterative organization of information and insights, leading to

evolving intellectual products that are continuously available for editing and

annotation - in that same workspace - by all peers and instructors. The value of such software has been

reviewed by Sherry et al. (2000) and many predecessors.

With a little imagination, teachers and students can use SDCC as a medium for MOOS, in which they create separate workspaces that metaphorically represent "rooms" that contain unique objects and activities.

Later in this chapter, I will give some examples of

how I have used SDCC to enhance the effectiveness of my teaching.

Available Software

The kind of document sharing that I am talking about

is found with several commercial software systems. Most of these have been designed for corporations and

government. It is hard to find

such products from Internet search engines, because they are called by

different names: enterprise solutions, Web conferencing, meetingware, project

ware, or peer-to-peer netware.

Moreover, the names donít mean the same thing to everyone. Examples of systems that are

potentially applicable to teaching include E-room (http://www.documentum.com/eroom/),

Hummingbird (http://www.hummingbird.com/role/default/home.html),

NextPage (http://www.nextpage.com/), and

WebEx (http://www.webex.com/). However, these systems are

expensive. WebEx, for example,

costs $6,000 to set up and $100 per user per month. And some of these systems require extensive support

infrastructure.

My colleagues and I at Texas A&M first attempted

a simple, low-cost way to create a SDCC system, which we wanted to use in our

teaching. Our original

software (FORUM) allowed students to create community documents, provided

all the in-context linking capability of Web pages, and did several things that

Web pages cannot easily do: 1) accommodate independent teams of learners, 2)

create workspaces for private individuals or groups, 3) provide variable levels

of shared access permissions to any given document, and 4) support pop-up

in-context sticky notes (writing in the margins). FORUM was limited in that it required client software

installation that was cumbersome, and the documents were formatted in a non-standard

word processor and not coded in html.

However, we have now have a SDCC system (called Forum

MATRIX (www.foruminc.com) that has most of the software needed on a Web

server. The only thing needed by

users is a Web browser and Microsoft Word, both of which are already possessed

by the vast majority of computer users.

Personal Interaction On-line: Conversation

Theory

Why It Matters

Conversation is central to learning and to

community building. In on-line

environments, conversation is in writing.

Written conversation engages students with content more rigorously than

does speaking.

Teachers who truly believe that reading and writing

are important to the educational process should surely embrace on-line

conversation. I have even found

that on-line conversation enriches traditional face-to-face teaching. Formal studies have shown that students

who use the most primitive on-line communication mode, e-mail, produced more

writing, developed a larger vocabulary, and attained a greater awareness of

group process (Mehus, 1995).

On-line conversation yields an archive for reflection

and later use in different contexts.

Also, asynchronous conversations can be more comprehensive than

face-to-face conversation, because it is not constrained by the serial turn taking

where only one person can speak at a time. Instead, on-line conversations occur in parallel, and there

is no limit on responding to multiple lines of thought. According to Knowlton et al. (2000),

the advantages of properly administered on-line conversations are:

…

Learners do not feel so isolated

…

Learners can build relationships that help motivation

…

Everyone has a chance to be "heard"

…

Shared perspective and background knowledge make

learning broader and deeper

…

Ideas and facts can be pursued at deeper and more

thoughtful levels

…

Views and information are subject to re-examination

and update

…

When the conversations are asynchronous, as they

often are in on-line instruction, several other advantages apply, compared to

on-line chats

…

Schedule conflicts are avoided and learning is more

convenient

…

More time becomes available for research and

reflection

…

Multiple patterns of discourse develop in parallel

…

Data and commentary can be organized optimally, rather than "on the fly."

The communication between instructor and student and student-to-student

communication serves many learning functions: rehearsal of factual information

to expedite memorization, exposure to a broader range of information, deeper

understanding that emerges from consideration of alternative points of view,

stimulus for creative thought, and growth in information management and

learning skills.

Why should teachers require a richer level of

conversation from their students?

John Chaffee, in his book The Thinkerís Way (1998),

states it in a way that reminds us teachers of our obligations to

students:

"We show the most respect for people by holding them to intellectual standards of rigor and honesty, informed by knowledge and reflection. And in doing so, we encourage them to make the effort to elevate their understanding, instead of being satisfied with superficial and misguided ways of thinking."

Building

community through asynchronous on-line interaction requires us to think about

how people should work together.

Because of the asynchronous nature, we are constrained to written and

graphic media. Our understanding of how to do written "conversation" should be informed by conversation theory.

In a

distance learning environment, optimal learning depends on the way that

instructors use conversation to mediate and enrich learning. Amazingly little analysis of conversation theory has occurred in the distance learning community, despite the fact that the on-line "discussion board" is widely accepted as an essential part of a distance learning experience.

Herein we will consider conversation theory as it applies to enriching

on-line conversation in distance learning.

Conversation Theory Overview

Patrick Jenlink and Alison Carr (1996) at Penn State University have summarized

the essence of contemporary conversation theory in the context of

education. They describe four

types of conversation:

1.

Discussion - exchange of opinion and

supposition. Positions, sometimes

rigid, are staked out.

2.

Dialogue - a community-building form of shared

viewpoints. Individual advocacy

tends to be minimized to achieve group consensus.

3. Dialectic

- conversation is aimed at distilling truth or correctness from logical

argument. Focus on analytical

thought and factual information.

4. Construction ("Design") - conversation aimed at creating something new, often in the form producing some kind of deliverable.

The other three forms of conversation are used as tools to achieve a

specified purpose.

Dialectic and construction forms require higher

levels of thought and are therefore the most educationally valuable. Sherry et al. (2000) consider "discussion" to be degenerate.

Application to Asynchronous On-line Learning

Most distance learning courses have a "discussion board" component where students converse with each other by posting notes. But on-line discussions can be like a

party that nobody comes to ... or a party where people are dressed wrong ... or

a party where they bring the wrong kind of presents ... or a party where a

drunk spoils it all with his boorish behavior.

On-line dialectic has not been widely used in

distance education. Socrates, were

he alive today, would certainly find a way to take advantage of the

opportunities for reflection and research afforded by asynchronous

telecommunication. Possible asynchronous

solutions might begin with a professorís question, to which students

independently post answers. To

incorporate the construction conversational element, students could then debate

and jointly edit all commentary to produce a group answer. The professor would then post a

follow-up question and the process repeats. The professor can also "write in the margin" of the posts with in-context sticky notes or links to Web resources that students need to inspect.

A direct approach for using the construction type of

conversation on line is to assign a group task, directing that all on-line

commentary be geared toward producing the desired deliverable. Examples include problem-based

learning, case studies, brainstorming and insight exercises, portfolios, and

projects of various sorts.

Making Conversation Constructive

Teachers regard the teaching of critical thinking

skills as among their highest calling.

Yet, we seldom understand the role that conversational style plays in

critical thinking. Chaffee (1988)

points out that critical thinking in group settings occurs when each

participant does all of the following:

…

Expresses views clearly

with supporting evidence and logic

…

Listens carefully to

others, weighing their evidence and logic

…

Stays focused on the

issues raised by others rather than on your own position

…

Asks relevant questions

and then tries to answer the questions

…

Strives for increased

understanding

Sadly, these conditions are seldom met in typical

on-line discussions, where the typical requirement is to require each student

to make a minimum number of postings in response to topic statements made by

the teacher. Such discussions are

conducted without an explicitly meaningful mission and group deliverable. How does that help the student to grow

intellectually?

When on-line conversations are task-oriented, the

learning becomes constructivist.

An over-simplified definition of constructivism is that it is learning

by doing. In application, this

means that the conversation results in some kind of academic deliverable,

commonly such as proposals, plans, designs, reports/papers, case studies,

debates, ideas from brainstorming, decisions, portfolios, brochures, kiosks,

hyperstories, or a variety of special projects.

Central to constructivist theory is the idea that

learning involves active engagement of students in constructing their own

knowledge and understanding.

Constructivism is learner-centered, rather than teacher centered.

Constructivism has three components: epistemic

conflict, self-reflection, and self-regulation (Forman and Pufall, 1988). Epistemic conflict occurs when a

learner is presented with a problem that needs to be solved that is outside the

learnerís current repertoire.

Resolution requires the active engagement of the learner, and is

enhanced by joint engagement with other learners. Self-reflection is the learnerís response to conflict. The learner must attempt to identify

the problem explicitly and objectively.

Self-regulation is the process whereby the learner adjusts and

reconstructs thinking to deal with the learning problem at hand.

For example, in my neuroscience course, one of the

students was a very bright electrical engineer with expertise in electronic

neural networks. The issues that

we raised in our class required him to re-think the information processing that

occurs in electronic networks in the context of how nervous systems process

information. He had to "reconstruct" his knowledge and experience, in the face of conflicting evidence about how computers work and how brains work. His adjustments to these conflicts were reflected in the

shared documents that his group was constructing, not only enriching his own

understanding of neural networks but also creating whole new dimensions of

thought for the more biologically oriented students. His thinking became accessible to the other students in ways

that would never occur in a typical lecture class.

Action Verbs That Make Good Conversation Happen

Another way to think about constructivist conversation is to specify certain action verbs that require the active construction of understanding, knowledge, and insight. Words that are particularly useful for on-line conversation include:

… Identify

…

Compare and contrast\

…

Explain

…

Argue

…

Decide

…

Design

Identify

Students can develop their ability to observe and

discern when they are required to identify relevant facts or issues. Examples: 1) Identify the root causes

of the U.S. Civil War, 2) Identify the criteria by which we decide whether or

not a given brain chemical is a neurotransmitter.

Compare and Contrast

This classical educational device requires students

to recognize similarities and dissimilarities. It extends the "identify" requirement through further analysis. Examples: 1) Compare and

contrast the way computers work and the way brains work. 2) Compare and contrast Netwonís view

of gravity with that of Einstein.

Explain

Teachers have always known that the best way to

understand something is to explain it to their students. Students likewise gain understanding

from explaining complex ideas to fellow students. Examples: 1) Explain what a mathematical derivative is. 2) Explain why the Soviet Union

collapsed.

Argue

John Chaffee contends that the central reasoning tool

required to analyze complex issues is to construct and evaluate arguments. He does not mean to argue in the sense

of quarreling. Rather, the central

value of constructing arguments is the need for mustering evidence and logic

that can stand scrutiny. Examples:

1) Why should we consider nitric oxide to be a neurotransmitter, even though it

is a gas? 2) Why shouldnít the

United States embrace European socialism?

Decide

What could be more important than the ability to make

wise decisions? Making decisions

often is the culmination of earlier steps of identify, compare and contrast,

explain, and argue. Examples in

academic curricula might include: 1) Determine the requirements for a

cost-effective light rail system; 2) Decide which line of research in molecular

genetics shows the greatest promise for immediate benefit. Do we have any systematic way to teach

decision making to young people in most academic curricula? Group-based decision-making is common

practice in the business world, and the processes are taught systematically in

Business colleges. Why isnít

group-based decision making an important skill to learn in other

curricula? It IS important in the

real world outside of school.

Design

Both creativity and critical thinking are stimulated

when students are asked to design something. This tactic is standard fare in Engineering curricula. But the learning benefits could also be

available in other disciplines.

Examples include: 1) Develop a plan to test the hypothesis that .....;

2) design a Table of Contents for a book on ...........

Responding positively to such action verbs takes

conversation to a new level far beyond the mere expression of opinion. This is especially true when the

learning activities are conducted by groups of students operating under true

team conditions.

Group

(Team) Learning

Team learning in on-line computer conferences is widely practiced, and I am convinced that it is very effective (Kaye, 1991). When performance occurs in learner groups where the insights are shared, not only is learning elevated but students also learn to become more effective socially. Individual achievement in the real world typically depends on how well a person can work with other people. Some students are more effective group learners than others, and my experience has been that all students need improvement in this area. This is most conspicuous with students in competitive educational tracks, such as pre-professional (law, medicine) or graduate school. Such students became competitive for admission to selective professional or graduate schools because they compete (not cooperate) well. But in the real world of their professions, they will suddenly find a need to work collaboratively. Most young lawyers work for large law firms with a large stable of diverse clients. Physicians depend on a staff of bookkeepers, receptionists, technicians, nurses, and often other physicians in group practices. The "mad" scientist working alone in her ivory tower is a myth. Scientists typically work in teams, and they must always network with peers in their field to cultivate a reputation, get published in the best journals, secure prestigious positions and awards, and obtain grant funding. Complex communication skills are often more important for success in life than expertise or the traditional idea of intelligence (Goleman, 1995).

Advantages

Group learning is an important way to improve

learning outcomes and to make learning more enjoyable. Humans are social animals, yet

traditional classroom instruction often treats students in isolation. In response, educational reformers

created a group- or team-learning model in which small groups of students were

organized as social groups dedicated to helping each other learn the

instructional material. This

reform movement began in traditional classroom environments. Paradoxically, group learning has not

captured the imagination of many distance educators, despite the fact that it

is distance learners that need the social reinforcement and motivation more

than classroom learners who do have social opportunities outside of class.

Group learning in traditional classrooms has its

critics. Many teachers object to

giving group grades, even though the teacher always makes the grading rules,

which can include individual grading.

Students commonly complain because the work is not evenly shared among

group members. Underperforming

students can cause superior students to get a lower grade than they think they

deserve. Likewise, the

contributions of superior students are not usually recognized. All these objections arise when faculty

do not know how to conduct group learning properly. A proper group-learning environment stresses teamwork. The guidelines for creating a spirit of

team cooperation and coordination are provided in the next section.

Why is team learning not more widely practiced in

distance learning environments? No

doubt, distance educators have the same bias against group learning as

classroom educators. I know that some of this bias derives from a common belief that group learning is "kid’s stuff," appropriate only for elementary school. Too many professors apparently do not know how vital

teamwork is in the world of business and government. If we are training professionals to have the appropriate

academic background for careers in business or government, why are we not also

training them to develop the social/political skills to apply the academic

content in real-world environments?

Then, there are teachers who remember bad

group-learning experiences that were improperly conducted by their own teachers

who did not know how to conduct team-learning classes. Or, they hear "horror stories" from their students who groan in complaint at the prospect of having another bad group-learning experience.

Paradoxically, many distance educators do not realize that technology

overcomes the major obstacles to effective team learning in face-to-face

classes.

What are these better ways for team learning that are

provided by distance education technologies? Let me summarize:

…

Every studentís work is seen by everyone else in the

group and by the teacher. No

student can hide or coast unnoticed on the work of others. Everyone can see who is doing good work

and contributing to team success.

…

Asynchronous collaboration makes it harder for overly

assertive students to dominate the group activity, because on-line environments

make it easy for each member to contribute without interruption or

intimidation.

…

Because all work is documented in electronic text and

graphics, the group (and teacher) can readily monitor progress on assignments.

…

Schedule conflicts create no problem. Each student can submit work and review

the work of others at any time within designated deadlines.

These advantages are so apparent that I have used

on-line asynchronous group learning as an adjunct to my face-to-face class (classes.cvm.tamu.edu/vaph451),

which I have been doing successfully for about 10 years. Of course, I also use team learning in

my Internet course (classes.cvm.tamu.edu/bims470).

Team learning can not only promote learning, but also

build relationships that can last long beyond graduation. These relationships go beyond being

merely social, because a group learning experience helps students to learn the

talents and educational capabilities of group members in ways that are not

possible in a traditional face-to-face class that does not employ team

learning.

Collaboration Formalisms

The requirements for effective group learning have

been formalized (Cooper et al. 1991; Goodsell et al. 1992; Kadell and Keehner,

1994), and many teachers recognize the enriched learning experiences provided

by collaborative learning(CL). But

formal CL is not generally practiced in on-line environments, although the idea

is certainly not new (Kaye, 1991; Klemm, 1995).

Teamwork is a central element of this learning

style. Effective CL requires that

students be positively interdependent on one another (Johnson and Johnson,

1989). Assigning complementary

roles to each team member helps assure that learning objectives are understood

and appreciated by everyone. In

on-line learning, collaboration provides social and intellectual support that

would otherwise be available only in face-to-face classes. Distance learners must be disciplined

and motivated in order to cope with the relatively impersonal instruction that

occurs via distance technologies.

My

University Teaching Experiences

With Shared-Document Conferencing

Because of the complexity and cost of existing SDCC

systems, my colleagues and I at Texas A&M University have created

collaboration software called Forum MATRIX, which is licensed for commercial

distribution (www.foruminc.com). The name derives from the fact that the

software enables a forum wherein documents, which reside on a central Web

server, are organized by a matrix of links. The software runs in the standard Web browsers. The only client software needed is a

browser (Netscape or IE ñ recent editions) and MS Word (2000 or XP), which most

people already have or can get inexpensively.

A

server-side MYSQL database contains information on who the students are,

student log-in ID and password, whether there are groupings of students into

autonomous learning teams, what activities and documents they have access to,

what level of access they have (no access, read only, read-write), and

identification of the documents and their hierarchical relationships. Permissions can be set by individual or by group, and permissions can be changed "on the fly," as for example when the teacher is ready for each group to see the work of other groups.

The interface appearing in the browser window

simultaneously displays a navigation tree of the organization of documents and

also a display of the Web page that corresponds to the selected item in the

navigation tree. All documents are Web pages that already exist on the Web (the one illustrated is a default page (created in MATRIX) that appears before an item for viewing has been selected) (Figure 3).

Students

not only can view the scrollable documents in their Web browser, but most

importantly, they can check a document out for inserting text and graphics,

editing, or for making links (to Web sites, MATRIX documents, or to pop-up

notes). Documents are saved in MS

Word and in html format. The documents are not only archived on the Web server, but when a student checks out a document, our Word macro allows the "Save As" function so that a document copy can be sent to a selectable folder on the hard drive or any portable media.